Italian Records and their Geographic Differences

Researching Italian records can be particularly rewarding when we consider that for generations people would remain in the same town. It is part of the Italian culture to settle in one place marrying people from within the same community, living in the same ancestral home and carrying on the same trade for generations. As a result, today we can trace a family as far back as the late 1500s by researching records in the same town.

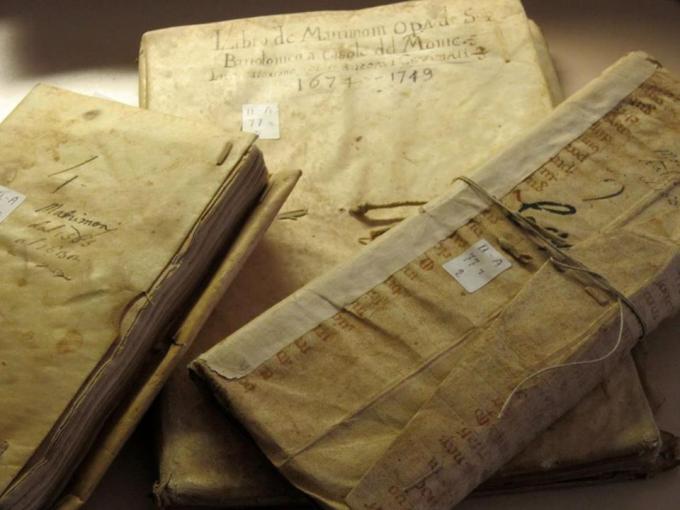

The oldest records are the parish church records that were introduced after the Council of Trento in 1595; that marked the division of the population into parishes (i.e. parrocchie) where each priest was required to record baptism, marriage and death of every parishioner. To this day, a parish church could serve one town, a group of small villages or one neighborhood in a large city.

All records were handwritten and although each priest wrote in the language he desired, the preferred one was Latin. These are mostly unique records.

Two and a half centuries later, it was Napoleon Bonaparte who conquered a large part of Italy and introduced very important changes to most of the areas under his control. With the Napoleonic code, civil acts of birth, marriage and death started to be recorded in the local town hall (i.e. municipio) by town hall officials in a more standardized fashion and in duplicate copy. Despite the effort to introduce this practice throughout Italy, only southern regions, mainly the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (from Campania down to Sicily, part of Tuscany, Lazio, Abruzzi and Molise) established the civil record system as early as 1809 (Sicily started in 1820).

We will have to wait until after the unification of Italy around 1870 for this practice to become official throughout Italy, i.e. central and northern regions. The dual-recording by both “state” and “church” initially created some confusion among people who, until the state was able to enforce its authority, were reluctant to declare and register their marriage, births and deaths in the local town halls according to the new rules. Eventually people adapted to the new system, which slowly became the official one.

Because vital records are kept at the local level throughout Italy, you must know the exact “town-of-origin” to conduct a family research project. Once you discover and verify the proper town you can then determine where the records are best kept, for instance: the year the local municipality started the civil record system, the condition of the records and what is missing if anything. You may need to make contact with the local church for older records and this gets more complicated when the town has more than one parish church. For instance, in large cities such as Salerno or Firenze, although the civil records are kept in one location, the towns have respectively 40 and 111 churches to choose from for the older parish records. On the other hand, smaller towns such as Marigliano (Naples) has seven while Salcito (Campobasso) has only one.

If your ancestor came from a southern Italian town, odds are that research records from the 1800s will be performed in the local town hall records. If he or she came from a northern Italian town, then the research will have to be split between the town hall and the local mother church and obtaining access in both sources can be difficult and time consuming.

Let My Italian Family Do The Work For You!

Give us a call! We offer a FREE Telephone Consultation for applicants who have questions regarding qualification, required documentation, estimated cost, timelines, and tips on how to make an appointment with an Italian Consulate here in the U.S. (among other questions). We will also perform some free preliminary research to establish if you have a path to Italian Citizenship! Call us at 1-844-741-0848, we are ALWAYS OPEN!

Alternatively, you can book your FREE consultation at your convenience.

At My Italian Family, we provide FULL assistance, handling all the purchasing and preparation of your entire portfolio of documents, whether you apply at an Italian Consulate here in the U.S. or you apply in Italy (including 1948 Challenge Courts Cases). Our experience spans 20 years, and we have expert knowledge of what each Italian Consulate requires and what the Italian Courts require. TO GET STARTED AND FOR MORE INFORMATION, CLICK HERE.